CHORIZOSFRONTERIZOS | BORDERLINKS

a personal reflection with actualities

by James Bradley – Summer 1992

“I’ve a pain from I don’t know where,/ That comes from I don’t know what./ I’ll be cured I don’t know when / By someone whose name I forgot.” 1

For Borders, there are no simple geographical facts.

Think about Israel, Kashmir, the “former Yugoslavia”, or even Chiapas. Underlying the question of a person’s or a people’s geographical origins, is the assumption that knowing where someone is from will provide useful, perhaps even decisive, information about who they are. It is a perilous assumption, but it exists in the conventional vocabulary of interpersonal encounters.

A border is a line. It is a line that divides. It is the meeting place of two (or more). It has two faces. A border is also an area where the two (or more) overlap, mix. While the terms of the designation are, strictly-speaking, geographical, the message is ontological: let me tell you about myself, about who I am, about my divisions and my multiplicity. It does not imply a singular, cohesive, unalloyed existence.

I’m identified with a border. So much so that, when asked by someone, “Where are you from?” My answer, more often than not — if I want to give someone some bearings, some cultural clues — is something like this: “I am from the Border (i.e. Borderlands)”. Or, if I really wanted them to have something to think about, I’d say, “I was born in San Diego, like my mother and my mother’s father, and raised in the foothills East of there along the Mexican border.” Not the US Border, or US-Mexico Border, but the “Mexican” Border, as if to emphasize the relationship with the “other” country, the proximity of the “foreign”. I must need, desire, this affirmation of an otherwise unstated fact, a complicated elaboration of my origins.

If the questioner were from Europe, Asia or Africa, the variables in the construction would depend upon where we were, who posed the question, what I wanted them to know, what their interests or intent was perceived to be, and so on. If they were Mexican, the formulation would be a little different, it might be: “Soy de la frontera norte, en California.” While they might reasonably ask, “¿Baja o Alta?”, they usually don’t, because they know I’m not Mexican. There might also be some confusion about the designation “frontera norte,” because for residents of Mexico, as of the US, if you say you are from The Border there follows a possessive assumption that you mean their Border, meaning their side of the border.

It sometimes occurs to me that it is my geographical distance from “The Border” that contributes to the character of my identification with the region. It may produce a kind of nostalgia for, a romantic attachment to, the distant object whose “reality” is part imagination, part memory, part encounter. While distance may be a crucial factor in this relationship of subject to object, it certainly is not a simple constant — it must depend on other factors — since I move toward it and away from it, into and out of it, on a more or less continual basis. Four to six months away from the zone is the maximum temporal distance for me these days.

In Restaurante El Romanico

around the corner on Madison Street in Lower Manhattan, I waited for my sanwich cubano to finish toasting and listened to a young Transit Police Officer, “Morales” on his name plate — a dominicano like the restaurant proprietor — narrate a recent incident: Two youths were on the F-Train returning to Brooklyn about 9:30 on a Thursday evening — the stores are open late on Thursdays — when they get the bright idea to rip-off this ‘Rican woman with a big bag of gifts from Macy’s — it being her daughter’s quinceañera in two days. So one Mutt grabs the bag and the other puts a knife to the woman’s throat. They timed it just as the train was coming to its stop at East Broadway. Then they drag the woman — who is still holding onto the bag — out of the subway car. Or try to, because she’s not making any noise to speak of, what with the knife and all, but she’s being stubborn about giving up that fucking bag. So they pull her part way out, but they get caught in the closing door. One guy is on the inside with the bag being held by the woman who is stuck in the door being held by the second guy with the knife still held to the woman’s face.

In the meantime, a young Chinese woman with a baby has alerted the token-booth clerk above on the Mezzanine level that something was happening down on the station platform. The Clerk radios in and I get the call. I’m having coffee and flan de coco in here with my partner, you know Louie, right? It’s only about a block away, so we jump out of here and run toward the corner, to Rutgers and Madison where the South exit is. Now here’s our first problem: this is a huge station, I mean it’s almost three blocks long and it has four exits. So I tell Louie to go down the first one, there at Madison and I run up Rutgers toward East Broadway and Canal. Now I don’t know at this moment if anybody else had responded to the call, there could be a car nearby, but we know that those fucks from NYPD are not going to respond to a TPD dispatch, so I’m running and I’m trying to decide which hole to go down.

Now I can see all three exits from where I am as I get to the first one there next to Wing Shing’s and so I’m eye-balling them all to see if anybody is running out, but there’s nobody moving fast, just a couple of old Hassids and a couple of unisex Punkers. So I go into this decision mode, you know where I gotta do it and do it quick because I don’t know what’s happening down in there if any body’s been killed or hurt, just the possibility — and I know that once I commit, once I go down one hole, the perp can be playing rabbit out one of the other two — I know too that Louie’s moving up the underground connector from Madison and he’s going to be right about even with me now, so that’s the same as me going in the first entrance, so I run across East Broadway toward Seward Park, because I figure that if somebody goes out the West side they gotta go past the Token Booth and the clerk will spot ’em and be able to ID them later, so I cut my losses a little that way, but if they go out the North end of the station, they could go out by way of the turn-stile that the Clerk can’t see, so they’d be away clean, so that’s what I do, I head for that one. Just as I get to the subway stairs, I hear this fucking NYPD chopper come over the tree-tops of the park, like they was some kinda Rambos comin’ in to save my ass. I mean they don’t ever do nothing for us transit guys except by accident of some kind of whim or something, but all this is distracting me for a few seconds. So I make my move down the stairway when up comes this little asshole conejo negro and he runs right into me, “BAM!” and I’m down on the ground, flat on my own ass with this little Hip-Hop on top of me. He’s lookin’ scared and doesn’t know what’s happenin’ any better than I do. But I already have my stick out, so I just whacked him once and drag him back down into the station, ‘cuff him, and then walk him back down to the mezzanine token booth. I don’t know how much of this those guys in the ‘copter see and I don’t much care. I mean, I’ve made a better-looking collar in my life, right?

It is more than twenty years since I have resided in the Border region:

not living there day to day, not being drawn into the quotidian flow of repetitious transactions and minute, numbing detail. It is through this degree of distance that I have sustained my liaison. And too, I have remained a reasonably faithful lover by refusing to accept the permanency or inevitability of my estrangement. I refuse the casual attribution of “New Yorker” and have managed to retain a valid California Driver’s License. But this preoccupation with identities and attributes, of domiciles and derivations, is part, I think, of a larger dynamic in which I am caught up, as many of us are. It is a kind of crisis of identity that affects each of us. While this so-called crisis is not uniformly acknowledged as a personal, let alone a global problem; and while it certainly affects people differently, depending on their particulars (e.g. locale, class, gender), it appears to be undeniable. It is so, despite it being a medically, or psychologically questionable category of crisis.

My father died rather unexpectedly.

He called, San Diego to New York, to inform me — late on the night before he went into the hospital — of his plan to have elective surgery, heart valve replacement. He ran down the medical contingencies (not including death), the quality-of-life concerns, the conclusions by his MD and the consulting Cardiologist of his 99% success rate. It was a monologue, like a pep talk — more for his own benefit than for mine — to pump-up the team before the big game: a bigger game than he was willing or able to imagine. The operation was a success, but he didn’t survive.

The Telophase Society people were already at work with my father’s body by the time my sister called me with the news later that day . And when I arrived the next afternoon from New York, my sister and I, after leaving the Airport, took a short detour. We easily found the low, commercial building. I went in, gave my name, my father’s name, signed a release form, took a copy, went through a side door into a kind of shipping area where a smiling young man, who looked vaguely Filipino, was waiting with a neatly wrapped, brown paper package about the size of a large, squarish loaf of bread. On a neatly typed label was my Father’s full name. It was his false full name. It gave “Edward” as the middle name, which he adopted at some point because he was dissatisfied with his given middle name, “Elijah”: the name of his great-grandfather, and of a few other male ancestors in his Father’s Old-Testament-loving family. My mother thinks that it was a problem for him because it sounded too “Jewish”.

I carried the package unceremoniously out to the car, and put it in the trunk. We then proceeded to her house in Oceanside where my mother was waiting and, where, as my sister informed me, family and friends of “the deceased” would be gathering in a few hours for a wake. The Irish traditional mode had already begun to emerge, with the replacement of the dead one’s given name for the epithet (“our dear brother”) or later for the substitutive pronoun (“Himself” or, simply, “He”).

My grandmother, the Irish Matriarch of my father’s family, was not present. She was not told about her only son’s death. Not yet, she was still too frail. “Fragile” is the word they used, too fragile from her hospitalization for the fall she had taken two months earlier. Her guardians, the aunts who were my father’s sisters, would not allow any word to get to her now. But the five of them came to my sister’s home. So did many of their daughters, their husbands, their daughters’ children and husbands. Some of my father’s closest friends came, too. There were not many. His closest friend from high school days was there early. He came in with a bottle of Tequila in each hand. His wife carried some flowers and a mesh-bag full of lemons.

The blood relations were polite and respectful to my mother, although she had always had a problem with them because she was their only sister-in-law. She was not Irish. She wasn’t blood kin. They were unusually restrained. Their characteristic buoyancy and gregariousness was dampened by the occasion. There were no old-timers there. There was no one there who knew the old ways of the wake, who knew how to keen and when to roll up the rugs for the dancing.

My father’s oldest friend came up to me at one point and handed me a glass full of the Agave-juice. He raised his own glass in a silent toast. He waited for me. Then I raised my glass. He smiled, closed his eyes, and while still held closed, swallowed his drink at one shot. I followed suit. Eyes open, he touched me on the shoulder and asked, “Did your Dad ever tell you about the time that we took that horse out to El Centro?” Not waiting for my response, he continued: “He almost got himself married to a Mexican gal on that trip. I bet he didn’t tell you that part. We had gotten ourselves invited to dance at a big house, a hacienda, below Mexicali, so we went…”

The brown box stayed in the car the rest of that day and well into the next. By then the wake was over. Without a body, it was very untraditional and was not allowed to pass by without notice or comment by my aunts, who didn’t really approve at all of the incorporeality of the situation. The lack of a body was unnatural. Or, at the least it was a hastening of the inevitable reduction of our flesh to the basic elements which everybody knew took place, but not with such express rapidity.

Only after the wake did the immediate family — mother, sister, brother and I — discuss what to do with Ken’s ashes. Ken hadn’t specified what their disposition should be, unlike some people who ask that the ashes be scattered at sea or out of an airplane over a volcano, or whatever they could pay for or arrange with the Telophase people or with friends or accomplices. We couldn’t come to an agreement. Not that there was a great deal of discord, it was simply that there was no consensus. No one wanted it to be dragged out though, so we did reach an agreement on a plan. We would all drive together, East out of San Diego, up into the mountains where we had spent various parts of our lives and where my father had tried to be a horseman and rancher, to where we knew we could find an appropriate place.

The more I think about this “Border”

the more I am confused by its complexity. As time goes by, it becomes increasingly difficult to sort out the place it has in my life and to disentangle the layers and levels of its significance. If I proposed to define myself in terms of geographical origins, as I previously suggested, it was with the knowledge that such tactical acts of description or attribution were in no way adequate to the larger task at hand. While I may choose to acknowledge my birthplace and the locale of my upbringing, the character and circumstances of my parents and ancestry, these details are not necessarily the defining ones, despite being essential elements.

I was a Caucasian male baby weighing seven pounds twelve ounces at my personal beginnings. The hands of Catholic nuns first held me and cradled my newly-sprung body. It was wartime. A first-born child to my mother, who was healthy, although she had waited six years after her marriage to get pregnant. She had been diagnosed with Tuberculosis in her teens and waited until there were no signs of the affliction. Not essential.

Her people were mongrel, Euro-Americans (English, Irish, French, Welsh, Scots). My father’s people were nominally Irish American (Irish, English). Her people were principally farmers, although they diversified over the years. His people’s ancestors were mostly peasant farmers, but they too learned to do other things in this country. His father had been a truck driver, policeman, factory worker, janitor, civil servant. By the time I was born, my father had been a salesman, factory worker, and rancher. My mother’s family arrived in the area just after the Civil War. My father’s family came just before the Depression. My people were white, primarily working class.

This is part of the inventory: the data and descriptive detail I accrue, draw upon. It is my laboratory, as well, where I go to examine the elementary and cumulative make-up of the personal and the historical. I may be able to cite the inventory of family genealogical knowledge or sociological profile, but the nature of its historical reality is in contextual dynamics, between and among individuals, groups, nations. In these expanded terms, the regions that now lie along the line of demarcation between the US and Mexico are as rich, as rewarding — and as confounding — as any I’ve encountered anywhere. But, of course, I am biased.

It took us a couple of hours to make our way

— start, stop, deviate, return, advance — until we found ourselves about seven miles South of Interstate 8, at a sharp bend in the county road that goes down past Morena village to Cameron’s Corners, just above Campo. Beyond this nearly-ninety-degree bend is a small bridge under which flows — except in the Late Summer and early Fall — a creek that feeds Lake Morena, just out of view to the South-South-West. Also at that bend is a dirt surfaced, branch road, which dead-ends about a mile West at Camp Morena, a State-operated, low-security, labor camp. Just after the turn-off to the Camp, down a steep incline, there is a smaller creek. It feeds the larger one that flows beneath the bridge crossing, which flows into Lake Morena, then down to Otay Lakes, into the Sweetwater River and, eventually, into the Pacific Ocean less than fifty miles distant.

Everyone was getting a little weary from the drive and didn’t mind the stop. We got out of the car, took the package from the trunk and walked down the dirt bank into the shade of Black Oak, Sycamore, Cottonwood and Willow. We found a clear spot and sat down together on lichen-covered granite slabs. Nearby, the shallow delicacy of the water, in some places a mere glaze of transparent liquid, flowed over the same rock bed. Against the bank we had descended were shin-deep accumulations of mulching leaves from the surrounding trees. The most basic elements and processes of nature were evident in this place, without elaboration or adornment, without grand spectacle or visual drama. It was all there. The four of us understood.

I opened the package and exposed the ashes. The sediment wasn’t as fine as I had imagined. Instead, it was a coarse amalgam of different textures and shades of grainy, gray matter with bits and pieces of splintered, charred bone interspersed. I almost expected to find a dental bridge or a St. Christopher medal inside the box, just like the prizes we’d find in the crackerjack boxes at the El Cajon Theater when I was a boy. Carrying the box a little way downstream, I sprinkled a portion of the ashes out in front of me over the ground, the water, and the leaf mulch. Then I handed the box to my sister who walked a little farther along and did the same. In turn, my brother and my mother did the same.

“Look here Professor, if the line, this here, the border, slides a little over here, Mexico doesn’t lose much of anything — what are a few meters? — and we would find ourselves on the other side and — now we’ve made it! We work like legals and we have school and welfare, or have medical insurance and unemployment.” 2

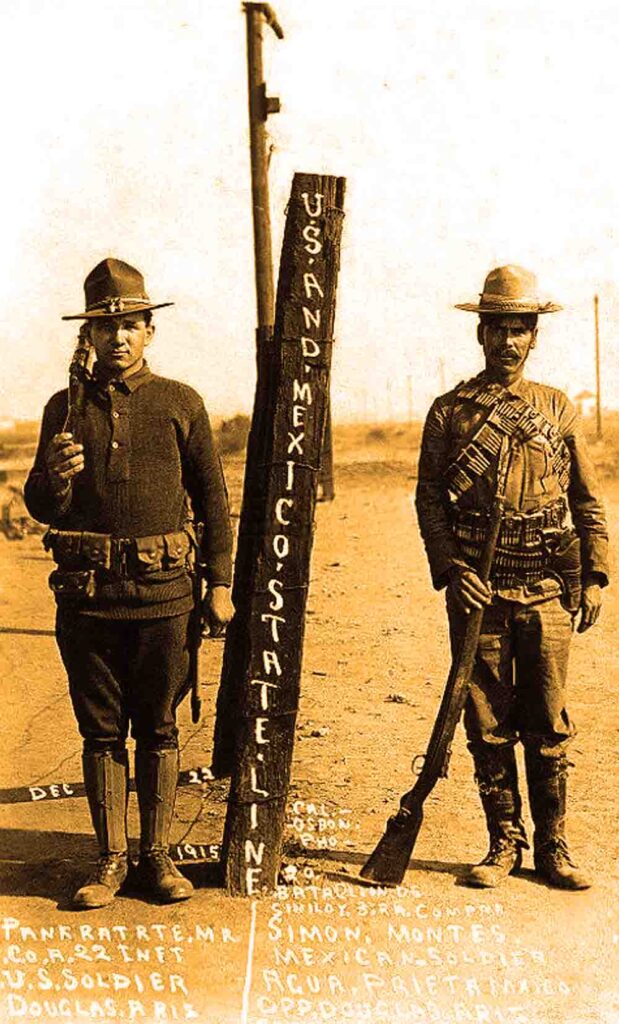

The border is about land first and foremost.

It defines land. And it defines the power implied by the control of land. As in such expressions as, “Watch out buddy, that’s my real estate!” Land is also, obviously, property. In being acted upon by political and economic forces it defines territory, a broader concept of “land” and its subsets: sovereignty, control, influence. The Mexico-US Border, as we know it, is an extremely arbitrary line of demarcation. It does not entirely follow the features of the landscape, except along the Rio Grande (rio bravo). It was produced out of war and treaty. Yet, even then, it did not correspond to the lines of military conquest or occupation. No fence bounds its delineation, except in populated sections. It is acknowledged to varying degrees, in the conscious behavior of those who people its regions. The principal determinants lie in the specific, albeit changing, character of the bordering peoples, states, nations. The defining characteristics of the US-Mexico border are, in large part, the direct and indirect result of the exercise of economic, political and military power over Mexico.

In Mexico’s national archives, there lies the Border Treaty between Guatemala and Mexico. It is “zealously guarded” in a “luxurious cabinet” and “elegantly bound”. Whereas, in stark contrast, the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which defined most of the border between the US and Mexico, is in a file that has, somehow, been misplaced. The explanation offered is that the first is seen as having benefited the nation, while the second is viewed as having “stained its honor” (manchado su honor). 3

Mexico’s Southern border with Guatemala has long been the site of migration by indigenous groups (esp. Quiché, Mam, Kanjobal), who move in both directions, yet it lacks the pressurized economic and political character of the Northern border. And with a very few exceptions, as during the counter-insurgency sweeps by the Guatemalan Army in the early to mid-80s, there is little military presence or show of force there. Were Guatemala a more vibrant economy or a more distinct political and social culture, then the dynamics along that border would be definably different. If for instance, the peasant-dominated insurgencies in Chiapas lead to more rapid economic development, through federal grants and investments, and/or integration of the region into the NAFTA-led national and international economies, we would without doubt witness corresponding changes in the dynamics of that border region.

In the US, “The Mexican War” dossier, along with its accompanying files on the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, Gadsden Purchase and “La Mesilla”, have been thrown away. In part, because it was, retrospectively, viewed by many in the US as an embarrassing and sordid chapter in this nation’s history — an example of self-justification and naked expansion that produced a one-sided, unprincipled war of conquest. But it must be recalled, that war was still chivalric in the middle of the 19th century. At least, it was before the US Civil War. And for a suitable war, one needed a suitable adversary. Bellicose apologists in the US did their utmost to paint a picture of Mexico as a noble culture, an inheritor of Spanish colonial glory, which had a menacing, European-trained army. This calculated description was disseminated in order to elevate the stature of Mexico as an enemy. But it never quite worked. The profile didn’t fit. Mexico was a “sister republic” — a smaller, weaker, internally-divided neighbor. Mexico did not invade US territory. We invaded hers. Mexico did not provoke the war, the US ensured that Mexico had to fight or simply succumbed ignobly to the assault.

Canto,/ Cantemos,/ para que no se detenga jamás el sonido de estos / pasos estallando,/ haciendo trizas el pasado,/ el brillo de las bayonetas bordeando las fronteras / como una muralla de madres protectoras / celosamente cuidando a su criatura. 4

About five months before my own father’s death,

I stood with several other North Americans in the center of a bald, powdery dirt, soccer field in the northern Nicaragua village of Ocotal. A massive, billboard-sized mural, in colors of red, white and black stood starkly at one end of the field. A roughly constructed platform, like an elevated stage, stretched out in front of the billboard, as if the theater’s set included the assembled audience. There were small clusters of camouflaged Army and Militia troops ranged loosely, informally at its flanks. A few old, grisly men with broad-brimmed straw hats and wearing red and white scarves around their necks, sat stiffly in folding chairs arranged in several rows on the stage. They were accompanied by young children, in bare feet, wearing shorts and freshly-washed, neatly pressed white shirts and the same scarves as their elders. Officials of the government arrived, tie-less, short-sleeved shirts, informal. There were few people in the field, only a thin scattering, standing idly by or in small groups conversing, quiet and dignified.

Suddenly, a kind of murmuring, low rushing sound began to surround us. As if on some silent signal, the time had arrived. Although it was not matched to an even number on a clock, the community, or rather clusters of small neighboring communities, of which this was the center, mobilized and spilled into this small playground from all sides. They carried their own seating. Most were old wooden, folding chairs, the kind you’d see in small churches or rented meeting halls, or they carried boxes or cushions. Whole families came, school classes came in assembly lines, tradesmen, workers from construction projects arrived, having just put down their tools. Many of the women carried brightly-colored umbrellas to shade themselves from the intense sunlight. With the people also came animals, dogs and goats, an occasional bird and food and drinks of various kinds.

This was the day of commemoration for their national hero, Augusto César Sandino. Not on the day of his birth, as we would do it in the US, but on the day — February 21st, 1934 — when he was assassinated.

I was there as part of a small group of what the Nicaraguans called intelectuales — writers, artists, filmmakers, musicians — who had been invited by the ASTC (Asociación Sandinista de Trabajadores Culturales), the cultural worker’s union. We were to tour the country and see first-hand what the Revolution was doing for the people of Nicaragua.

The day before we had stood with the young guardafronteras who showed us the partially-exploded RPG shells, made in the USA, that had been fired at them from the Honduran side of the border. From where we stood, we could see that border less than 50 meters north. We could see the observation post, set-up on a hill to the East, which, we were told, was not Honduran Army, but manned by one of the Contra groups funded by the US. While we talked, a Toyota pick-up pulled up from below us. Four young Sandinista milicias, teenage girls and boys carried the rojinegro draped body of a compañero, killed the previous night, out to the awaiting truck to be taken to his hometown for burial.

Since the inauguration of a Contra offensive along the northern border out of sanctuaries in Honduras, terrible things were being done to these people in the name of the US. Most of us had come to bear witness to these events, to see who these people were that were being targeted as enemies of our country; to expand our understanding of this small nation’s people, who were being represented in our homeland as fanatics, dangerous terrorists, exporters of war and a threat to their neighbors.

Most of our small group had come out of New York, but two had come from Los Angeles. Both were Chicano: L was a print journalist, and the other, M, was a poet, who had been born and raised, or as he put it, “had survived” the East LA Barrio. The neighborhood of his early childhood had been in Chavez Ravine, razed to make way for the construction of Dodger Stadium. Both of his parents had emigrated from Morélia during World War II and had stayed in the North and made the best life they could. But he had carried the illusion of his being able to go back to Mexico if he chose to, if things got too bad in the States. He confessed that he had fallen in love with these people and their revolution, because, he said, they were a nation of poets and their revolution was made by poets.

In the US, there is no public celebration of a victory over Mexico.

To do so, even symbolically, would perpetually allow for the question to be asked: “why are we celebrating such an ignominious act?” And besides, it would be redundant. The national consciousness, which is that of the Victor, provides constant, daily reproduction of the earlier conquest by our “noble” civilization over their “lesser” one. The US has proved, through its economic expansion and development, its superior qualities as a national culture. It can say, “If we took land that belonged to someone else, we might be a little uncomfortable about it, but we have proven beyond the shadow of a doubt — look at Mexico’s under-development, its lack of competitiveness — that we were better able to make the world fruitful for having done the deed. We’re not proud of what we did to the Indians or the Mexicans. But, after all, we had a mission to fulfill and we did the best job we knew how.”

In the debates in the US legislature following the victory of US forces, there was a concerted effort to seize all of Mexico, which would have put the southern border of the US at Guatemala! If the decision proved to be less radical, it was due to a great degree, not to a lack of acquisitiveness on the part of the gringos, but to a reluctance to bring polluting blood into their national flock: “if we annex the land, we must take the population along with it. And shall we…by an act of Congress, convert the black, white, red, mongrel, miserable population of Mexico — the Mexicans, Indians, Mulattoes, Mestizos, Chinos, Zambos, Quinteros — into free and enlightened American citizens, entitled to all the privileges which we enjoy?” 5

Most Americans at the time appeared to be of the opinion that annexing Mexico would mean either the instant acquisition of nearly 8 million new non-Anglo-Saxon citizens, or that the US would become, overnight a new, major colonial power with the same eight million subjects. It was ruled unacceptable. But that was in the mid-19th century. By the end of the century, following the 1898 war, there had emerged a more sophisticated concept of colonialism, that would prove serviceable well into the third-quarter of the 20th century, in such places as the Philippines, Nicaragua, Vietnam, Panama.

From the beginnings of a US national culture, the rhetoric of expansion (Westward Ho!, Manifest Destiny), while quite naked in its first two hundred years, was always accompanied by a moral objective: to bring “civilization” to the heathen (barbarian, savage). Harnessed to national economic and political agendas by the end of the 19th century, the concept of “New Frontier” — an endless series of frontier challenges — where “civilization” and “conquest” were fused into a sophisticated, multi-dimensional strategy aimed at the control of markets.

M had spent more than eighteen years in jails and prisons all over California. One of his most memorable busts came for taking part in the attempted robbery of a liquor store. He and one of his carnales were sent to a place called “Camp Morena,” which they were told was a “country club”, where they would get to spend a lot of time outdoors. This, to two city-boys, sounded like a good deal. After a few months of the hardest labor in the harshest conditions — long days in 100 plus degree sun — M and his buddy decided they had had enough. They decided to escape. And one night after lights-out and everybody was pretty much asleep, they made it out and over the fence, literally. It was not a very high-security establishment, so they easily made it. It was pitch black, no moon, and they couldn’t see much of anything, but they tried to make their way.

At first they didn’t recognize the noise. It sounded like tissue-paper being torn. They stopped for a moment and decided that it had to be rattlesnakes. Not just one, but choirs of them. Panicked, they ran. But the terrain and the Manzanita and Creosote bushes made it hard to move very fast. Running, tripping and falling, getting scratched up by the dense Chaparral, they got up and went at it again. It seemed like hours had passed before they tumbled down a dirt embankment onto hard flat rock, and into running water. They could hear it moving and feel its direction. Following it a little way along, they made out the dull outline of a low bridge. Once up onto it, they found themselves on the pavement of the County road they had worked on.

There they decided to split up. One went South toward Highway 94 and back toward San Diego. The other, M, went North toward the Interstate. By daylight, M had walked about fifteen miles: first north to the main highway and then East toward Jacumba and the drop down through Carrizo Gorge going toward Imperial Valley. He stayed close to the road so that he could possibly hitch a ride with a trucker or some local ranch hand in his pick-up. Instead, he was spotted by la migra, making his daily run along the East-West route: part of a routine search for illegales. And that, apparently, is what he thought when he spotted M. The agent took him into the back of the 4×4, spoke to him in very rudimentary Spanish and asked him where he was from and where he was going, where he crossed over, and who the pollero was who helped him.

M made a quick decision, a fateful one as it turned out. He didn’t speak to the man at first, but simply nodded or shook his head and eventually gave out a key Spanish word or phrase showing assent, denial or confusion. He realized that if not this guy, someone, if they heard his chicanismos, would know that he wasn’t truly Mexican. If he was going to pull off this con, he had to play “Dumb Mexican” all the way, but play it smart. He was taken to the Border Patrol station in Tecate, California. Fed and watered there, he was then transported in the back of a migra van with the wire-mesh windows, to a holding station in Calexico. From there, along with a bunch of his new compatriotas, he was loaded onto a bus and deported. They were taken all the way to the interior of the Republic. A day and a half later he found himself in Guanajuato. He was a stranger there, treated with suspicion. The people there made fun of his Spanish. They called him pocho. He had a hard time making himself understood.

He made a call to LA to arrange for a little money to be wired, and then followed the route of the other pollos North toward the border. He crossed at night at a point only a few miles from where he had been picked up by the migra. It was not the barrio, or prison, he later told me, that had made him a poet “for life”, but it was life’s irony.

The different ways the two national cultures

have handled their respective historical representations provide telling instruction and, perhaps more important, tools for the interpretation of contemporary attempts by each nation (read institutional, governmental apparatus) to “correct”, “adjust”, “redefine” their past relationship. The cultural myths and codified symbols produced by each national culture are the inherited terms with which the popular culture and individual language and consciousness translates the meaning of engagement of the one with the other. For each national culture, history has a different function. Just as for each sub-group, there is a different “culture”. In point of fact, the very visibility of culture is an index of the non-assimilated peoples. To be part of the dominant, “American”, nominally Anglo-Saxon culture, is to have no culture at all in a sense. This is not true by definition, but it is a demonstration of the success of the ideological effect of cultural domination. The result is a condition in which English, for example, is our language, George Washington is our founding father, a capitalist economy is our way of life, ad infinitum. The presence of an identifiable culture implies a failure of the national culture to absorb the subject; or a refusal by the subject to be absorbed.

A Chicano perspective on the so-called Border (which could reach beyond it, to Los Angeles, Chicago, New York) is offered by a noted anthropologist: “In ‘our’ everyday lives, cultural domination surfaces as a myriad mundane sites of cultural repression and personal humiliation. For ‘us,’ questions of culture encompass social analysis, and much more.” 6 From the dominant societies’ perspective, acculturation allows new immigrants to become absorbed into the “invisible” national culture — a process one critic calls “deculturation, a cultural stripping way” — in which national culture: “…erases their meaningful past — autobiography, history, heritage, language. Where José Rizal and Gregorio Cortez once stood, there shall be George Washington and the Texas Rangers.” 7

The wide-spread use of terms, like “illegal alien” and “undocumented worker” are manufactured, promoted and intended for consumption by those who see themselves part of the dominant culture. The residual ideological charge placed on these “aliens” is usually a dialectical mix of pity and rage that disposes many “assimilated” North Americans to nativist, racist reactions: “We let them in, and look what they do to us.” Or, “Look what we did for them, and this is how they repay us.” Recently, at a dinner in a famous Mexican restaurant in San Juan Capistrano, between bites of the enchiladas noted to be ex-President Nixon’s favorites, one of my cousins complained that there was a serious “Mexican problem”: “Those little brown beaner babies are crowding us out of our neighborhoods!”

T was already clear of customs

when I walked into Area B of the Delta Airline’s terminal at JFK. His eyes were red and crusty from long days and little sleep. Worn-out from his more than two months of coverage of the so-called Zapatista Insurrection (“el levantamiento armado”) in Chiapas. He would go out early in the morning from his house in San Cristóbal de Las Casas to outlying areas. Tramping around all day on foot, by car or microbus, he talked to people and took pictures. But by now, two of his cameras were broken, there was a lull between negotiations between the insurgent and the government; and he needed a break. So he came up to New York.

I wanted details, names, locations, an atlas of events and consequences to complete the predictably meager coverage one could compile out of the ITN, CNN, New York Times and such media staples here. T provided them with great enthusiasm and relish. I laid out my veteran maps. Using a pencil — I insisted on not permanently defacing the documents — he marked the principal areas under occupation or influence by the zapatistas. Some of the places were familiar: Altamirano, Ocosingo, Tonina, El Bosque. Others were more obscure, small communities or areas labeled on crude maps: Bachajon, Oxchuc, Simojovel. He charted out the zones of influence. Guadalupe Tepeyac, the headquarters of the EZLN. Comitán, where the Mexican Army was stationed. Where the largest land occupations had taken place. San Juan Chamula and Zinacantán, the traditional communities north of San Cristóbal, had not been directly drawn into the fighting. The Tojolabal and the Chol had been.

From the center of San Cristóbal, where the old oligarchy was centered, he built a diagram of the organization of the barrios that made up the town. The Quiché ladinos dominated one. Ladino chamulas and Zinacantanecos were among others. Each section of town had a distinct character and a well-defined relationship to the older established families and their networks of caciques and rancheros.

He described how, in recent times, a peasant group would send representatives to Tuxtla, the state capital, to inquire about the status of their land claim. If they were told, as they often were, that it was still under consideration; or, that it was impossible to say; or that their papers were lost; then these peasants would leave. Once back to their home area, they would gather together their family and their community, and report the news from Tuxtla. Then they would occupy the claimed land.

He was very knowledgeable about the area at the southern border. He’d been living there, more or less continuously, for the past twenty years. We joked about the fact that before this, before the first of the year, he had to go away to war, to the “hot spots” that were the staples of his particular brand of photojournalism. And he had gone. Not so very far: he was not a war junkie, or a globe-trotting image merchant. Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador: these were his stomping grounds. He was first in Nicaragua in ’80, then ’83, ’84, and again in ’86. He had published a fine book of images of la vida cotidiana in that troubled country. He covered the nasty US-financed insurgency along the Honduran border, walking for days in the jungle between Ocotal, Wiwilí and La Miskitia, along the Rio Coco, from Jinotega to the Atlantic Coast. He had gone to San Salvador and had been one of the foreign journalists inside the Capital when the guerrilla offensive hit. He came the closest there, he had confessed, to losing his life. He had seen the thing happen that should have killed him, but knew it had not for the flimsiest of reasons. In Chiapas, at first, he took refuge. Eventually he came to see the historical possibilities of the region. “Something big could happen here,” he had said to himself.

In returning to examine the chulas fronteras

as I do continuously — a fundamental objective in doing so, if it were to be set out with some precision, has been to re-construct its history. But in order to do so, I have found that history must be undone, in order to be done. Because I had begun to engage “my” history from the level of story, of narrative — through oral history and the collection of family anecdotes — I was not directly subject to the overarching narrative accounts of the Border region offered by the national culture. There were historical texts, but they were partial, fragmentary. I began to look, too, beyond my immediate family to find and collect other narratives, stories, experiences that accounted for the intimate and precise knowledge of this area and its early history. Working backward, working outward.

It was among the “Others” that the problematic character of a common history began to be clarified: among the older, middle-class, Mexican Americans, the Chicanos of my generation, the newly-arrived mexicanos, the Depression-era “Southern-Black” migrants, the Okies, the “Celto-Catholic,” American-born Irish, the third generation Chinese and second generation, Nisei, Japanese. It was from these and more that I came to derive a collection, an assemblage of historical material. The impact was decisive. No longer could there be a single, coherent account of these divergent experiences. At least, not one that was adequate to the task of incorporating the varied experience and factual detail afforded by the diversity. It is my conviction that this insight was the product of the Border. It was facilitated, propelled forward and validated in the experience.

The Border to which I return, or have not left, is a territory of difference — historical, ideological, linguistic — where each component competes for legitimacy. We may have to go through renewed traumas of sectarian division, even civil unrest, among ethnically, racially, even sexually distinct groups, before new possibilities or formations can emerge. The empowerment of historically subjugated or oppressed groups can result in the creation of “special interest groups”, cultural ghettos or cantons. But, it can also result in a new synthesis and fusion of identities and interests among and between groups. At present, I see no other coherent system of meaning, organized into political and economic power, that is positioned to replace the imperial past. Still, the history here, to which I continue to bear witness, can be instructive. It can offer critical insights into transcultural and transnational dynamics that are too often treated by the arbitrating national cultures, as nuisances or aberrations at its borders, “on the fringe”.

The war had come to T this time. It had walked right up to him and pointed its gun-barrel right into his face. Making his way home in the early morning of the new year, through the center of San Cristóbal, he saw figures in single-file columns wearing bandannas or ski masks over their faces converging upon the zócalo. He quickly managed to get home, load his cameras and returned to begin recording the dispersed, unfolding event. His pictures were among the first to be taken of the EZLN.

So we sat here at the table, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, speaking of the circumstances in Chiapas. We were interrupted a few times. A police helicopter was making furious, repeated passes overhead, close to the rooftops in our Loisaida-Hassidic-Chinatown barrio. It was very loud, very close. Something must have happened nearby to bring them. Not that there aren’t a myriad of reasons. The tape recorder had to be turned off on occasion, to take telephone calls. One from M, T’s wife in San Cristóbal de Las Casas checking in. Another was from his father-in-law requesting hard to find medication. One came from S, the Leica technician, to tell T that the camera he left with her would not be ready in time for his return to Mexico. He would have to find someone who was going to Mexico City reasonably soon, who would be reliable and willing to take the camera. T’s disappointment was evident, but he could manage. It wasn’t the first time we had to make such arrangements. Maybe the same person would be willing to bring additional film stock down as well.

We are witnessing the absorption of a once precise geographical term into the conceptual vocabulary of the marketplace. There are currently advertised: a Border Music, Border Art, Border Cuisine, and even a Border-Flavor. In the US, the term “Border” often becomes either an excuse for taking liberties with what was originally derived from Mexican sources, or for allowing a “no holds barred” intermixing of divergent styles and modes in a transparent amalgam.

Being of or from the Border can provide unique opportunities.

A great deal of vital cultural production comes from individuals and groups who have that accidental property of geographical derivation. If someone, like myself let’s say, chooses to write a novel, there is an opportunity to be taken by the author or by the agent/publisher to attach the attribute of “Border-ness” to the product. Thus my novel is “Border Literature” by virtue of my being of or from the Border. Now, the bearing of this purported quality of “border-ness” may be relatively incidental to the subjects or themes of the writing itself. Even the consciousness of the producer, while shaped by “Border” in some fashion, may have been overwhelmed by wildly divergent influences. But, if the active marketeer is sufficiently insistent, the work produced becomes “provocative, new, edge-pushing, envelope-stretching Border-Writing” — smack your lips!

What is true on one side of the border, does not necessarily obtain on the other.

There is no equivalent attraction for “Border-ness” at the heart of the Mexican cultural empire, where the chilangos often view the cultural production along the Northern Frontier with suspicion: an anarchistic, polluted, Calibanesque culture, running rampant from Tijuana to Matamoros. On the US side, at a comfortable distance (critical or geographical), the generalized view is that the border areas reflect demographic (read market) realities. The US national political culture seeks to co-opt and control the “Hispanic” electorate, while the private-sector extracts the benefit of the exportable attributes (border-things) and, at the same time, mobilizes the influential forces of group identification advertising to cultivate the consumption potential of the same sector of the population. Sociological definition and differentiation advantages mass market exploitation. Of course, the other major area of commodification is not, strictly speaking a “border” issue, but is the role of US tourist industries in colonizing the identity of another nation’s culture (emphasis on other, not nation) from San Diego to Cancún: “You too can own Mexico (for two weeks), buy the Ixtapa vacation package.”

Concurrent with, often in conscious response to, these cited developments is the increasing emergence of discursive text that might be loosely called “Border Theory”. Its project, it appears to me, is largely that of identifying the salient features of “border experience” that are perceived to affect (provoke) positive change in social consciousness and conduct. And, once identified (codified) in their symbolic, metaphoric, linguistic guises, to elaborate and incorporate these effects and devices into self-conscious, reflexive practice, or production. The result is a second-generation of Border-things that are produced with the express intent of exploiting the direct benefits the Border association, of “Border-ness” (Border as a cultural genre or tendency); or, of heightening the internal contradictions of the cultural product.

My, hopefully healthy, skepticism (sometimes verging on fear) of some of the theoretical propositions is heightened by cumulative observation of a kind of law of inevitability when it comes to such theories. The implication is that in positing an effect as produced out of Border experience, for example, one predicts the outcome of the effect — they desire it to be true. This suggests that, not only is the Border “effect” reproducible within conscious cultural production, but that a predicted occurrence is expected to be produced from that “effect”. Theory produces practice. Theory improves practice and practice improves theory. Practice also trashes theory. You know how the game goes: paper, scissors, rock.

However, as a community of on-again, off-again “theorists”, we have learned a number of very graphic lessons in our recent global history of theoretical models. I believe one such lesson is: Don’t generate or subscribe to theories that deny the spontaneous, inter-subjective actions of its subjects. Otherwise, you invite the rule of power, of the advantaged, theoretically, over those who, theoretically, don’t know the difference; or, if they do know the difference, can’t opt out of the consequences. No cultural theory is only cultural. It is also economic and social. To cite a recent historical example: the Sandinista Revolution, led by very sophisticated theorists of culture — Borge, Cardenal, Murillo, Ramirez, et. al. — while it mobilized immense cultural resources, which was inspirational to much of the Nicaraguan populace, it failed to successfully integrate the critical elements of the society, including diverse class and ethnic groups, into their national project.

The Borderlands have spread beyond their denotative origins to become every place we witness the rubbing up of multiple realities against each other. It is where the Russian Mafia wars with Chinese gangs in the city where I now reside. It is among the insurgents of Southern Mexico, “passed over” by the agrarian reform of Zapata’s revolution, who are now demanding to be factored into the national/international economies. It is among the “new” mexicanos and the “old” Chicanos, who contest the kind and degree of assimilation that will be tolerated as the price of participation in this country’s “project”. It is among the women of the “First World” and their sisters in the “Third”, unequal inheritors of feminist egalitarianism, who engage in a form of dialogue over their re-definition of roles and identities. It is among those, like myself, who are produced out of the contradictions within the dominant culture and between it and others long-dominated.

There may be a kind of romanticism operating in my attachment, my obsession, for the Border, but I pursue no convenient representation of its meanings, for they come in seemingly inexhaustible supply with the most dizzying blend of the repulsive with the succulent. I hold it close and try to possess it as if it were my own, as I offer it to anyone who will partake. Although by now, at that moment you are tempted to accept, it may already have been stolen, or it may never have been mine to give, for I, too, have been a thief.

So I drag this Mook along with me, kinda’ draggin him behind me.

My partner, Louie, is down in there, leaning against the booth huffin’-n-puffin’, trying to get his lost youth back. And when he sees me, he says, “I chased him up to you.” And I says to my partner — we’re friends by now, you know — so I says: “Fuck you, Louie.” About then this other Chink kid, excuse me Jenny, this Asian youth comes up from the lower level off one of the trains and says that there’s a woman down there who’s been hurt. So I go down, I can trust Louie with the Mutt and when I get down to the train platform, I see this woman who’s been cut on the face.

She’s lying on the ground, leaning against one of the columns and being held by the old Jewish woman, who’s wrapped some kind of scarf around her neck and part of her face. There’s blood all over them both. So I radio for an EMS ambulance and go over to try to talk with the woman. She’s kinda in shock, but is talking a lot and seems very alert, so that’s how I find out about what happened. She says that the kid who grabbed her stuff stayed on the train, ’cause when the other one cut her she let go of it and fell clear of the door as the train pulled away. She said that the one who hurt her then ran away and she pointed out the way I had come down.

So I wait with her until the EMS people come and they get her on a gurney and we go out together to the next level where Louie is making time with the Token Clerk, who’s not bad looking, and then I decide to check the perp out with the woman, whose name is Romelia, the same as my grandma’s, right? So I know this isn’t the best way to ID somebody, but I decided to just check it out. So I motion for the EMS people to stop and to Louis to walk the kid over and I say to this woman, who is still talking about the presents for her daughter, the cake she is baking for Saturday’s party, the priest who is making a special visit even though he’s had the flu, — the whole nine yards — so I ask her if this is the guy who hurt her — and she turns toward him, squints a little, turns away for a moment, turns back to me and then says: “No, that’s not the one. The other one was smaller and wore a jacket of one color, bright green, the same color as the dress mi hermana la esta cosiendo para mi hija. El no es…no es.”

So that was it, man. One fucking lot of shit. You know what I mean, right? You just never know what it’s going to be. The kid I collared was some kind of honors student at Seward Park High School on his way home from a computer show, right? A fucking computer show! The woman took microsurgery on her face, paid for by the welfare and the machetero got away clean and so did the kid with all the quinceañera presents. So whenever I come into this place and sit down for mi flan y cafecita, I know that I might get another call like that. After that little incident, Louie put in for disability and took early retirement. This is my new partner, she’s just come onto the force. Her name’s Jenny, Jenny Liu. Say hello!

###

CREDITS

“BorderLinks / ChorizosFronterizos: A Personal Essay with Actualities“, by James Bradley. Anthology selection from Border Lives / Vidas Fronterizas, Binational Press (San Diego, CA) – Summer, 1996 (ISBN 968-7326-20-4).

FOOTNOTES

- From a popular song, Madrid, 1882.

- Margarita Nolasco, Identidad Nacional,(cited in Frontera Norte, 1989, p.489). Interview [excerpt] of a resident of Tijuana, who had arrived from Aguascalientes. MX within the year.

[Original text: “mire maestra, si la linea, esto es, la frontera, se corre un poquito para acá, México no pierde gran cosa ¿qué son unos cuantos metros? y nosotros quedaríamos del otro lado y ¡ya la hicimos! Trabajamos como legales y tenemos escuela y welfare, o sea el seguro médico y de desocupación.”]

- José Carlos Melesio Nolasco, “La identidad nacional en las zonas fronterizas,” Frontera Norte, Chicanos, pachucos y cholos, comp.Luis Hernandez Palacios y Juan Manuel Sandoval, Mexico: Ancien Régime (UAZ, UAM), 1989, p. 492.

- Gioconda Belli, from “Cancion Al Nuevo Tiempo” (poem), truenos y arco iris, Managua: Editorial Nueva Nicaragua, 1982

- US Representative Edward C. Cabell, Congressional Globe, 30th Congress, 1st sess., p. 162 (Jan. 12, 1848). CF. Reginald Horsman, Race and Manifest Destiny: The Origins of American Racial Anglo-Saxonism, Cambridge: Harvard Univ. Press, 1981.

- Renato Rosaldo, Culture & Truth: The Remaking of Social Analysis. Boston: Beacon Press, 1989, p. 149

- Ibid. p. 209-10.